When the curtain came down on The Jam in late ’82 it was undoubtedly a relief for Weller. The intensity of their message was simply weighing too heavily on his young shoulders. The music just too constrictive for his burgeoning mind. It should have perhaps come as no surprise that his next musical venture was going to be lighter in tone.

When the curtain came down on The Jam in late ’82 it was undoubtedly a relief for Weller. The intensity of their message was simply weighing too heavily on his young shoulders. The music just too constrictive for his burgeoning mind. It should have perhaps come as no surprise that his next musical venture was going to be lighter in tone.

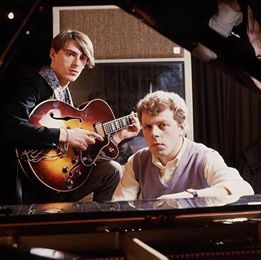

What was perhaps most shocking was just how adventurous and carefree he sounded on those early singles and albums. Formed almost immediately after the demise of his former charges Weller joined forces with South West Londoner (and fellow Mod) Mick Talbot, who had already played on a couple of Jam tracks (including, single The Eton Rifles) to rage against the Rock machine that had gone before.

Taking MacInnes’ Absolute Beginner’s template to Modernism the duo eschewed Parka’s for continental Alan Delon style cream macs and the monochromatic punk-rock xerox machine palette was swapped for vivid spruce green shirts and pillar-box red summer-weight knitwear. Gone were the stage-shoes and white terri-towelling socks and in came horse-bit suede loafers and correspondence toned tassel loafers; shoes so beautiful that socks were simply not needed.

The gritty high-rise and dirty-grey London town backdrops to their photo shoots were replaced first by the artful and romantic Parisienne streets; all Gauloise smoke, bitter espresso’s and La Monde newspapers before succumbing to the sun-kissed azure skies and fields of gold spun wheat, wind-blown scarlet poppies and dancing effervescent waterfalls of Europe’s capitals. Truly; The Style Council were a band that were broadening their horizons.

Musically, the pair of passionate Modernists did what all Modernists should do and magpied the best of everything, whilst adding their own personal twist. Debut single Speak Like a Child (March ’83) was the opening salvo with its title taken either from Herbie Hancock’s ’68 Blue Note album or the possibly the single by Tim Hardin, both of whom were influencing the pair at the time; It had a joyful soul swing married to an organ groove that mined from Surrender to the Rhythm by Brinsley Schwarz. It’s light-hearted video atop an open-top bus around the desolate fields of Wales was a long way from the claustrophobic intensity of The Jam. It shot up the charts before nestling at number 4.

Money Go Round (Part’s one and two) followed just a couple of months later. It’s title a steal from The Kinks (Lola verses The Powerman and the Money Go Round LP) and despite its taut slap-bass funk groove, trombone hook and half rap half socialist rant it is perhaps closer to The Jam sound than even later hit single Walls Come Tumbling Down – it really wouldn’t have been out of place on The Gift; alongside Precious or Transglobal Express. Far better was the track hidden away on the reverse of the 12” Headstart For Happiness.

This beautiful uplifting song defines the spirit of the band like no other – the stunning lyrics were the new manifesto for the new breed:

‘Naïve and wise with no sense of time, as I set my clock with a heart-beat, tick tock

Violent and mild, common-sense say’s I’m wild, with this mixed up fury, crazy beauty…’

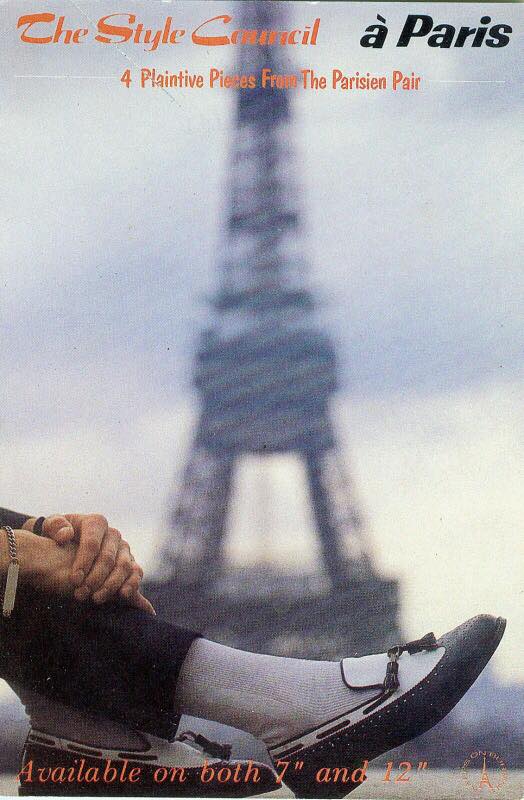

Lyrically Weller was in a purple patch, and the cinematic beauty of their next single, the bona-fide classic Long Hot Summer (title from 1958 Paul Newman film) was a huge hit across Europe – provisionally entitled the A Paris EP (plaintive pieces from the Parisian pair) it also contained one of Mick Talbot’s finest contributions Le Depart, which echoed the cinematic feel of the A-side.

Its video though was another nail in the Rock coffin – playful and coquettish and taking a visual lead from the homo-eroticism of Brideshead Revisited (not for the first time – check out the lyrics for Pity Poor Alfie) with a half-naked Weller fondling Mick Talbot’s earlobes to the synth bass-line soft bongo percussion of new drum lieutenant of just 17 summers Steve White – it had many a Jam fan spluttering into their Cappuccino. The single reached number 3 and became their highest chart position and deserved higher. A revisited and remixed version also charted in 1989.

Steve White also appeared on the follow-up single (and fourth in a year – imagine that now kids!!!) A Solid Bond In Your Heart, which like Money-Go-Round reached No 11, was another hark back to The Jam days. The song was actually written the year before and was vetoed as their swan-song in favour of The Beat Surrender. It sounded dated in comparison to what had preceded it and despite a wailing saxophone the four-to-the-floor Northern Soul stomp belonged a life-time away. Again, significantly better was the B-side It Just Came to Pieces in My Hands. Even the video seemed to be a throw-back to a Jam Mod image, although Weller’s hair in it is rightly considered as the definite Mod barnet.

Part Two To Follow

So, where to start; well I think the first mention in MOD terms, is the Roger Daltrey shoe that he wears in The High Numbers. There may have been others before, but this is the first photographic evidence I can see. As you can see in the pic, the shoe is white on the front and down to the sole. The lace is a derby style with 2 hole eyelets for the lace. The back part of the shoe is black.

So, where to start; well I think the first mention in MOD terms, is the Roger Daltrey shoe that he wears in The High Numbers. There may have been others before, but this is the first photographic evidence I can see. As you can see in the pic, the shoe is white on the front and down to the sole. The lace is a derby style with 2 hole eyelets for the lace. The back part of the shoe is black.

My thoughts on this look, great on Steve, but I don’t know that it has aged well.

My thoughts on this look, great on Steve, but I don’t know that it has aged well.

What I have always liked about the shoe, is that it firmly states “I am a MOD“. Now a lot would argue it is not MOD at all, but let’s not get into that. When you were 15, it was the uniform you needed with very clear boundries. Green Parka, Sta Prest , Fred Perry and pair of Jam shoes.

What I have always liked about the shoe, is that it firmly states “I am a MOD“. Now a lot would argue it is not MOD at all, but let’s not get into that. When you were 15, it was the uniform you needed with very clear boundries. Green Parka, Sta Prest , Fred Perry and pair of Jam shoes.